During the early 1800s, work in the United States began to change. More people moved from farms to cities to work in shops and factories. By around 1850, nearly half of all workers were employed in non-farm jobs in places like textile mills, shoe shops, and printing houses. Many workers faced low pay, very long days, and unsafe conditions. They began to ask if this matched the ideals of freedom and fairness they believed the new nation should protect.

Skilled workers such as printers, carpenters, and shoemakers were often the first to organize. In 1827, journeymen in Philadelphia created the Mechanics’ Union of Trade Associations. They later formed the General Trades’ Union. Similar groups appeared in New York and Boston. These early groups tried to protect wages and establish fair working hours. Many also acted like mutual aid societies, helping members who were sick, injured, or unemployed.

Workers soon realized that they had more power when they acted together. One important tool was the strike, when workers stopped working to demand change. Women weavers in Pawtucket walked out in 1824 after a wage cut and won better pay. Carpenters and other workers in Philadelphia joined a huge general strike in 1835 for a ten-hour workday. They marched through the streets and shut down much of the city until many employers agreed to shorter hours.

Women workers played a crucial role in the growing movement. Young women in New England textile mills went on strike in Lowell, Michigan, to protest wage cuts and rising rents. In 1836, they started the Factory Girls’ Association. Then, in 1845, they formed the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association to push for a ten-hour workday and better living conditions. They worked in strong solidarity to achieve these goals by organizing large petition drives and creating chapters in other mill towns. They also published their own writings on mill conditions and shared their stories with lawmakers.

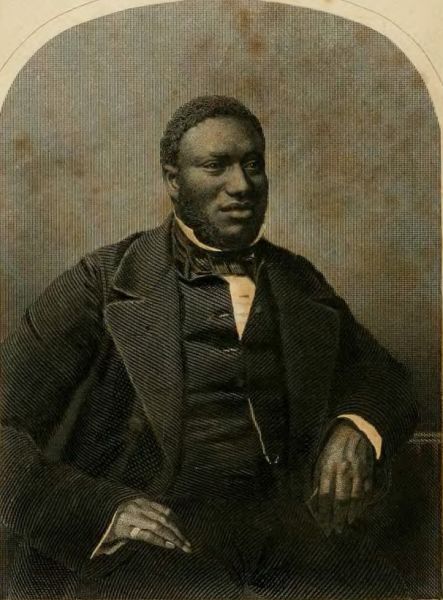

Black workers also organized. In 1850, Frederick Douglass and other leaders formed the American League of Colored Laborers. They did this because white unions often excluded Black workers. The group tried to build skills, support Black-owned businesses, and provide credit and loans.

Courts and lawmakers began to respond slowly. In 1840, federal workers on public projects gained a ten-hour day. In 1842, the case of Commonwealth v. Hunt in Massachusetts said that a union could be legal if it used lawful methods. By the eve of the Civil War, workers had formed unions and participated in strikes. This tradition of solidarity would shape the labor movement for years to come.