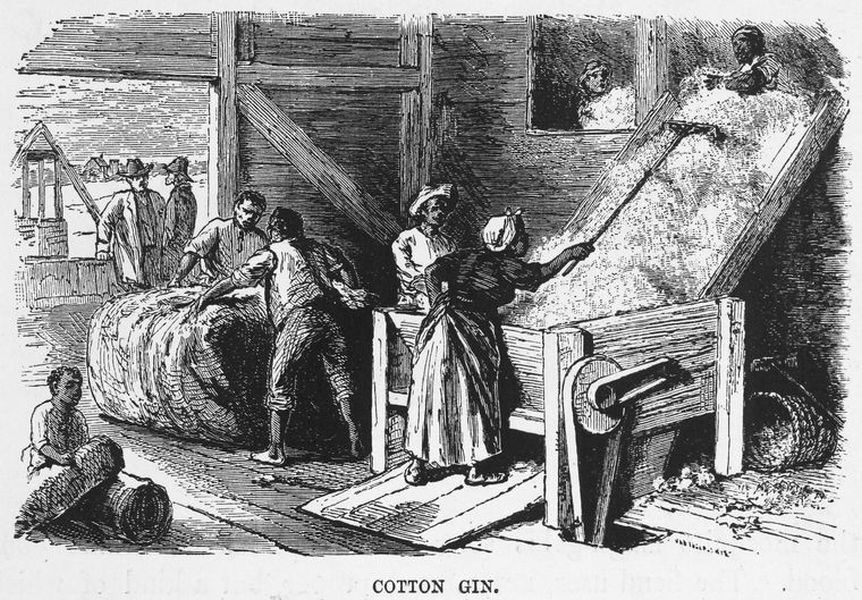

In the late 1700s, the United States began to move from a mostly agrarian economy to one that included more industry. This shift began when Samuel Slater built the first textile mill in Rhode Island in 1790. He used designs he had learned from British factories. Water and steam-powered machines made it easier and faster to produce cloth, iron, and tools. New inventions such as Eli Whitney’s cotton gin and his use of interchangeable parts helped make manufacturing quicker and less costly. These machines increased the amount of goods that could be made. Improvements in transportation, such as canals, steamboats, and railroads, connected farms and factories to more markets across the country.

Factories changed how work was done. In earlier times, people made goods by hand in their homes or in small shops. This new change meant that many goods were made in factories that brought large numbers of workers together in one place. In towns like Lowell, Massachusetts, whole communities grew around textile mills. Many of the workers were young women from nearby farms who came to earn wages. They often worked long hours in noisy, crowded buildings.

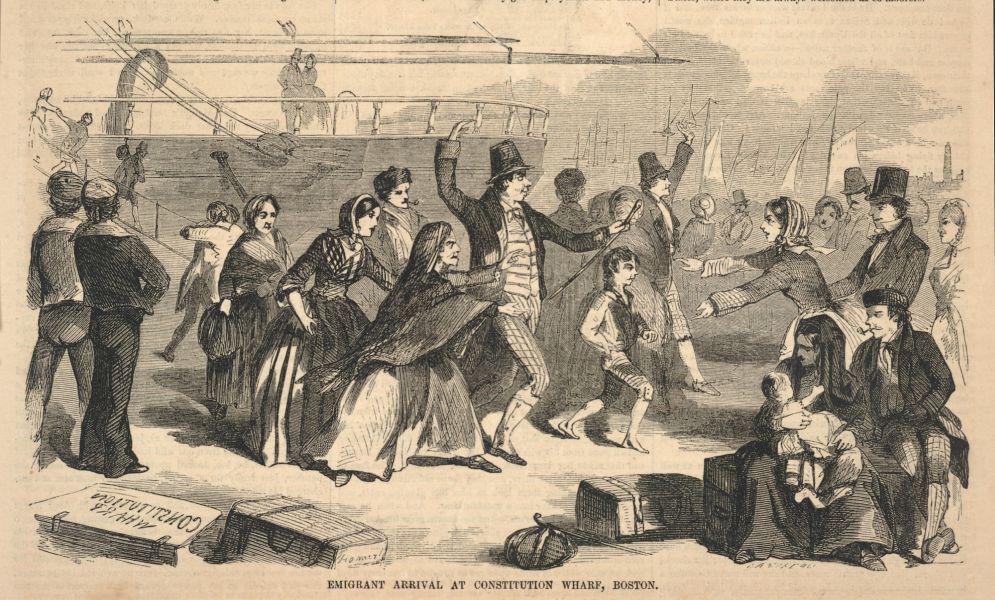

Enslaved Americans continued to work in the South, growing and picking cotton. This cotton supplied the northern textile mills. As the demand for cotton grew, slavery spread to new areas in the South. Cotton from southern plantations was shipped to northern factories, linking the two regions through trade. At the same time, immigrants from countries such as Ireland and Germany arrived to find work. Some helped build canals and railroads. Others worked in factories. Wages were low, and factory work could be dangerous.

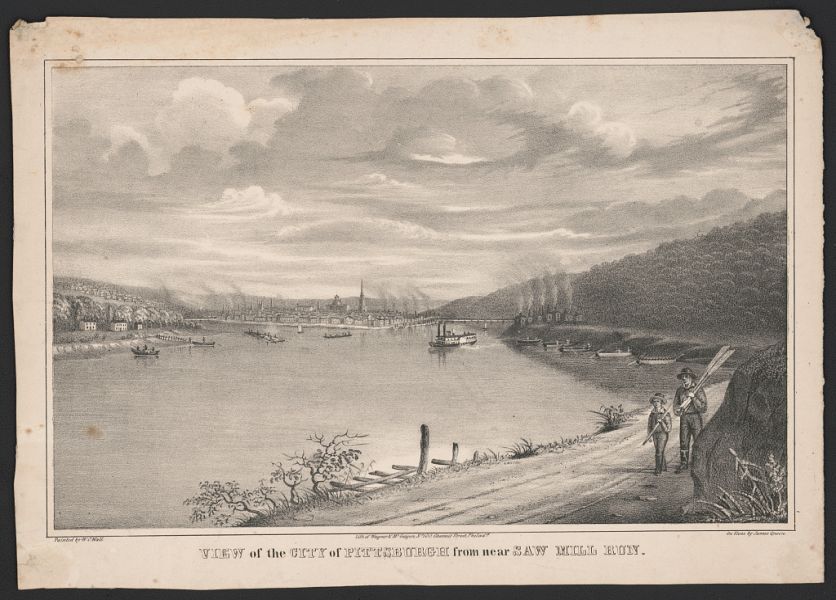

As American industry expanded, towns and cities grew. Mills were built along rivers, and new roads and canals made it easier to move goods. Many people left farms for cities to find steady jobs. Others stayed in rural areas to grow food and raw materials. Families adjusted to these new ways of living. Factory wages gave some people new independence, but many workers still faced long hours and few comforts. Women continued to manage homes, though many of the goods they once made were now produced in factories.

By the mid-1800s, the United States had become a country that mixed farming and industry. Machines, new kinds of work, and growing cities shaped how people lived and earned a living. At the same time, older systems such as slavery and small farming continued. These forces shaped the early pattern of American industrial life. This pattern continued to grow in the years that followed.