Cotton became the center of the Southern economy in the early years of the Industrial Revolution. New textile factories in Britain and other parts of Europe needed a steady supply of raw cotton to make cloth. The South had the perfect climate and soil for growing it. Plantation owners began producing more and more to meet the demand.

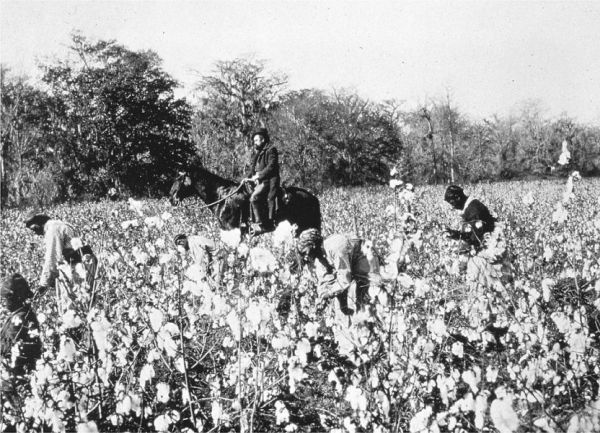

The cotton gin made cleaning cotton much faster. Because of this, plantation owners could grow larger crops and earn greater profits. As cotton production expanded, so did the use of enslaved labor. Plantation owners relied on enslaved people to plant, pick, and process the cotton. This created a system where nearly every aspect of Southern life centered around the crop.

The spread of cotton changed the geography of the South. Many enslaved people in the Upper South were sold to plantations farther south. States in the Deep South became the center of cotton production. This movement of people is sometimes called the Second Middle Passage. Families were torn apart as enslaved men, women, and children were sent to plantations to grow and process cotton.

The growth of cotton also changed cities and trade. New towns sprang up by rivers and railroads. This made it easier to ship cotton to Northern factories or ports for export. Cities like New Orleans, Mobile, and Memphis grew into key hubs for business and shipping. Banks and trading companies grew as they financed the buying and selling of land, cotton, and enslaved people.

Cotton brought great riches to some but came at a terrible human cost. It tied the Southern economy to slavery and limited the growth of other industries. The success of cotton farming also linked the South closely to global trade, as European demand continued to rise. By the middle of the 1800s, cotton had become both the source of the region’s wealth and a symbol of its deep social divisions.