In the middle of the nineteenth century, women in the United States lived under strict limits. Most women could not vote, serve on juries, or take part in government. Most jobs and schools were closed to them, and few churches allowed women to speak in public. Laws often treated women as dependents of their fathers or husbands. In many cases, anything a woman earned or owned legally belonged to a man.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were two reformers who wanted change. They met in 1840 at an anti-slavery meeting in London, where the male organizers refused to let women take part in the debates. The experience made them angry. It also strengthened their belief that women needed equal rights.

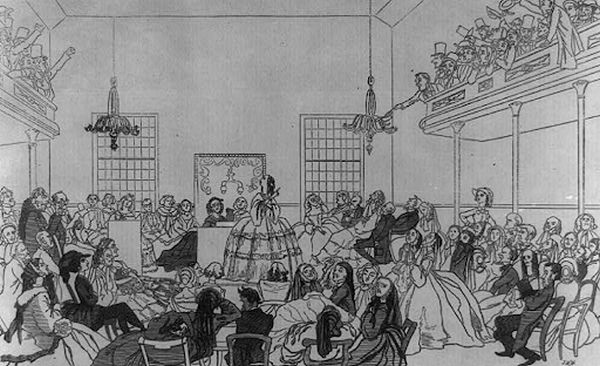

Eight years later, in the summer of 1848, Mott visited Stanton in Seneca Falls, New York. They planned a public meeting with friends to talk about women’s rights. The notice they placed in a local newspaper invited anyone interested in “the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman.” When the convention opened at the Wesleyan Chapel, nearly three hundred people crowded inside to listen and speak.

At the center of the meeting was a new document called the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, written mainly by Stanton. She modeled it on the nation’s founding Declaration of Independence to remind Americans that the promise of equality should apply to women as well as men. The declaration listed unfair laws and customs that denied women control over their property, wages, education, and participation in public life.

The resolutions that followed demanded equal treatment under the law and full citizenship. The most controversial proposal came from the suffragists, who demanded women have the right to vote. Some attendees found the idea too bold. However, abolitionist Frederick Douglass supported it. He argued that the vote was essential to protect every other right. After his speech, the resolution was passed by a narrow vote.

Public reaction was fierce and often mocking. Newspapers nationwide criticized the convention. They published the names of the signers to embarrass them. Some supporters withdrew after receiving harsh comments. Still, many others held strong to their decision. Publicity, even if negative, spread the story beyond Seneca Falls. It got more Americans thinking about women’s rights.

The convention focused on women's equality, yet some voices were missing. Black women, both free and enslaved, were rarely invited to take part in the discussions or planning. Many joined the abolition movement to fight for freedom and equality. They also organized locally. Their work often ran alongside, but separate from, campaigns led by white reformers. This showed how the early movement left some voices unheard.

Even with its limits, Seneca Falls marked a turning point. It opened up discussions about women's status in American society. It also urged the nation to uphold its ideals of liberty and justice. The convention did not solve every problem, but it began a conversation that continued to grow in the years ahead.