Transportation improvements powered the first phase of the American Industrial Revolution. New ways to move people and goods reduced costs, saved time, and connected farms, towns, and factories. These links helped factories get raw materials. They also let them send finished goods to faraway markets. Production increased as transportation costs fell and speeds improved. This helped the industrial economy grow.

Improved roads and turnpikes made overland travel more reliable. Wider, graded routes enabled wagons to haul heavier loads from town to town. Tollgates paid for road maintenance. Some states set standards for travel on the roads. This guided travelers on which roads were safe for wagons and stagecoaches. These roads helped local trade. They moved workers to new factory towns. They also linked inland communities to ports and river landings. This way, larger shipments could continue by water.

Water transport changed even more. Steamboats made two-way river traffic possible. Boats could now move freight upstream as well as down. This meant Western farmers could ship grain, lumber, and meat to Eastern markets and still receive tools, cloth, and other manufactured goods. Canals multiplied this effect. The Erie Canal linked the Great Lakes to the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean. Travel times fell, shipping costs dropped, and the volume of goods soared. Cities along these routes expanded. Ports like New York became key hubs for trade and finance. Factories could quickly send out goods and receive raw materials just as fast.

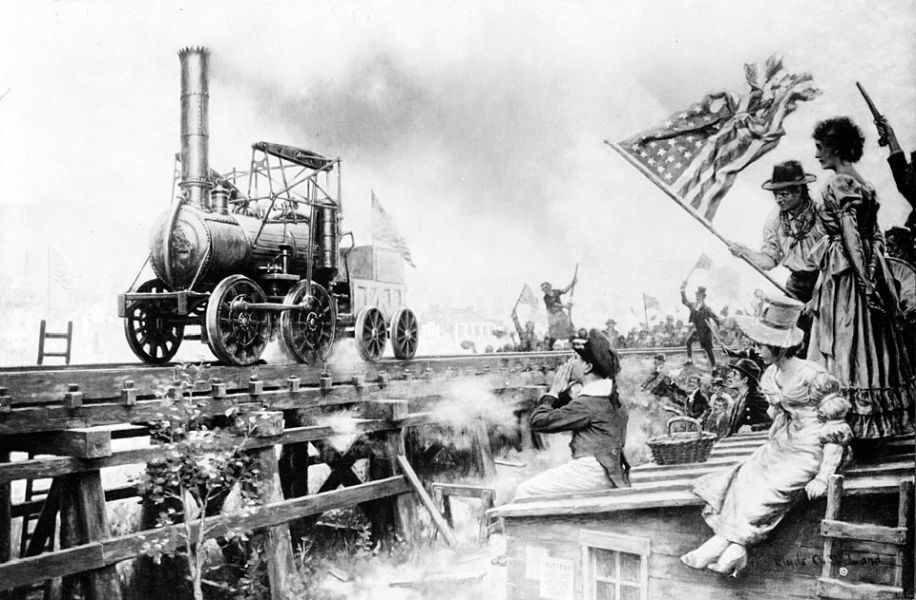

Railroads added speed and year-round service. Early lines, such as the Baltimore and Ohio, began in the late 1820s. By 1840 there were thousands of miles of track, and by 1860 tens of thousands. Trains carried coal from mines to ironworks and mills, which powered steam engines and furnaces. Railroads moved cotton, wheat, and timber to factories. They returned with tools, textiles, and other goods. Towns at rail junctions turned into shipping hubs and factories. Producers wanted quick transport, so they chose these locations. Telegraph lines along the tracks improved communication and coordination for shipping schedules.

Together, roads, rivers, canals, and railroads created a connected market. Farmers could sell to faraway cities. Factory owners could buy raw materials from distant areas. Freight moved faster, prices fell, and businesses could plan on steady supplies. The result was growth in production, trade, and urban centers. Transportation did not just follow industrialization. It helped the U.S. build a network to create a national industrial economy.