The Seneca Falls Convention marked the start of an organized women’s rights movement in the United States. Elizabeth Cady Stanton presented the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, calling for equal rights and women’s suffrage. That same year, New Jersey passed a law protecting the property of married women, showing early progress toward economic independence.

1849: Property Rights Expanded in California

When California became a state, its new constitution granted property rights to women. This step showed that ideas about women’s equality were spreading beyond the Northeast.

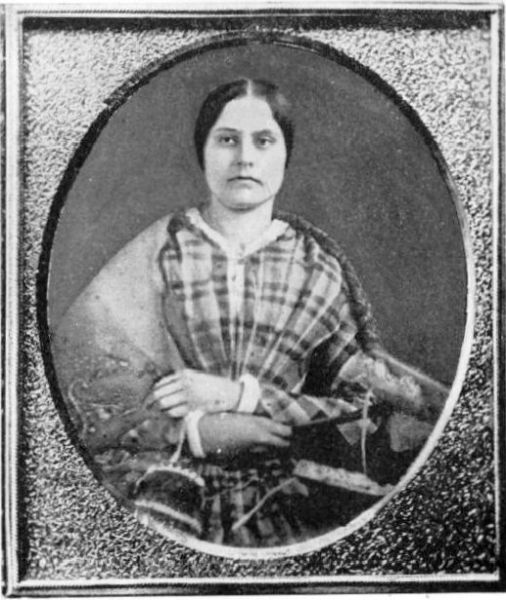

1850: The First National Women’s Rights Convention

More than 1,000 people gathered in Worcester, Massachusetts, for the first National Women’s Rights Convention. Speakers such as Lucy Stone, Abby Kelley Foster, and Sojourner Truth connected women’s rights to the fight against slavery. The meeting helped form a strong alliance between the women’s rights and abolitionist movements.

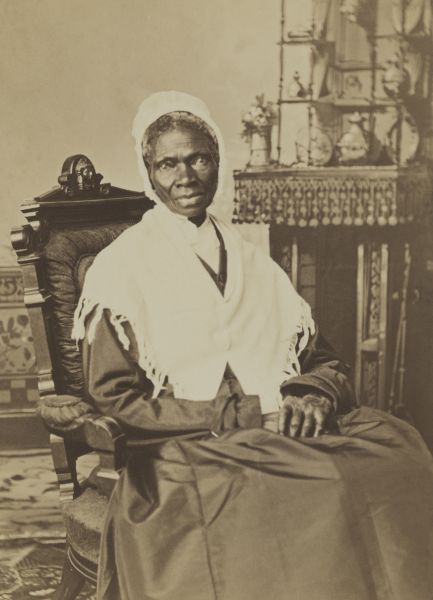

1851: Sojourner Truth Spoke Out

At a women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth delivered her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. Drawing on her life as a formerly enslaved woman, she challenged ideas about race, gender, and strength. Her speech became one of the most powerful calls for equality in American history.

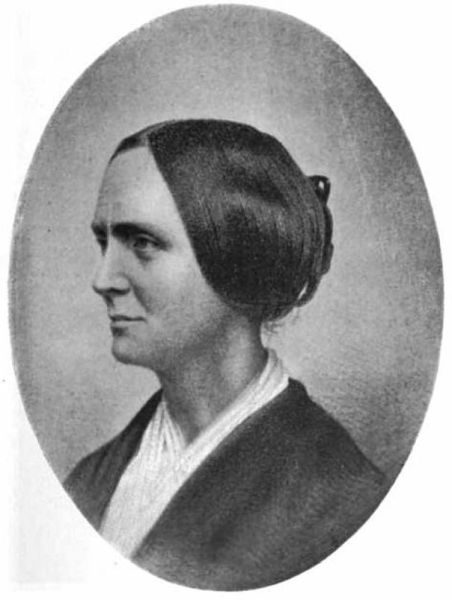

1852: Reformers Pushed for Property Rights

Reformer Clara Howard Nichols presented the issue of women’s property rights to the Vermont Senate. Across the country, reformers pushed for laws that allowed women to control their own property and earnings. In that year, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin hit the bestseller list. It linked women’s activism with the abolitionist movement.

1853: Women Were Barred from Speaking

At the World’s Temperance Convention in New York City, women delegates Antoinette Brown and Susan B. Anthony were not allowed to speak. The event reminded reformers that many social movements still excluded women, even when women worked for the same goals.

1854: Women Led Moral Reform Efforts in Cities

In growing cities like New York, poor housing and unsafe working conditions created sharp class divides. Members of the New York Female Moral Reform Society, many of them middle-class women, worked to improve city life. They raised funds to support working women, visited working-class families, and urged city leaders to pass laws against unsafe housing. Their efforts showed how women began to use organization and charity to address urban problems and take an active role in public reform.

1854–1856: Efforts Continued in State Legislatures

In New Jersey, reformers petitioned lawmakers to create legal equality between women and men. They were not successful, but their work kept women’s rights in the public eye. In 1856, universal white male suffrage became law in all states, further highlighting how far women remained from full citizenship.

1857: “No Taxation Without Representation”

Activist Lucy Stone refused to pay her property taxes, arguing that she should not be taxed without the right to vote. Her protest echoed the same principle that fueled the American Revolution. It linked women’s rights to the nation’s founding ideals.

By 1860: The Movement Grew

By the eve of the Civil War, women’s rights conventions had spread across the country. Reformers won some changes in property and divorce laws. However, they still faced strong pushback on suffrage. The debates begun at Seneca Falls continued to shape calls for freedom and equality for decades to come.