The Rise and Fall of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Born on the island of Corsica in 1769, he was a military officer who quickly gained fame during the wars that followed the revolution. As France struggled with political instability and war on multiple fronts, Napoleon used his popularity and military success to seize power in a coup in 1799. He declared himself First Consul, then later Emperor of the French in 1804. Although Napoleon claimed to defend the revolution, he also concentrated power in his own hands. He kept some revolutionary ideas—like legal equality and abolishing feudalism—but limited free speech and political opposition. His rule brought stability to a chaotic France and glory through military conquest. For a time, he dominated Europe, winning major victories and building an empire that spread from Spain to Poland.

By 1812, Napoleon controlled or influenced most of Europe. But his invasion of Russia that year marked the beginning of his downfall. Defeated by harsh winters and stretched supply lines, his army was left in ruins. A coalition of European powers—including Britain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia—joined forces to push back. In 1814, Napoleon was forced to abdicate and was exiled to the island of Elba. He briefly returned to power in 1815, but was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and sent into permanent exile.

Effects of the Napoleonic Wars on Europe

The Napoleonic Wars had a dramatic effect on Europe’s geography and politics. Borders were redrawn as empires rose and fell. Napoleon dissolved the Holy Roman Empire and reorganized German states, which later helped set the stage for German unification. In Spain, his invasion sparked a long resistance movement and the growth of nationalist ideas. Across the continent, people began to question the old monarchies and look toward more modern systems of government.

Socially, the wars spread revolutionary ideas that challenged traditional hierarchies. Napoleon’s Civil Code introduced legal equality for men and inspired reforms in countries he occupied. At the same time, his conquests caused immense destruction and suffering. Millions died in battle, and entire regions were left politically unstable. By the time of his final defeat, leaders across Europe were determined to prevent another figure like Napoleon from rising again.

The Congress of Vienna: Restoring Order

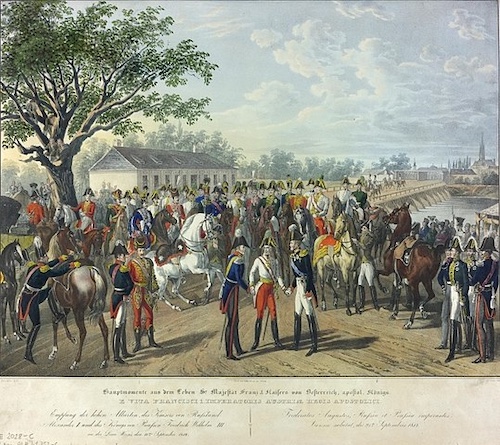

In 1815, diplomats from major European powers met at the Congress of Vienna to rebuild the continent after nearly 25 years of war. Led by Austrian statesman Prince Metternich, the Congress had two main goals: restore stability and prevent future revolutions.

To achieve this, they redrew the map of Europe to strengthen countries around France and prevent further aggression. France returned to its pre-revolutionary borders. The Congress restored monarchs to their thrones in France, Spain, and other nations—a policy known as legitimacy. To prevent future revolutions, leaders created a system called the Concert of Europe, where nations agreed to work together to maintain peace and suppress uprisings.

This effort to create a balance of power worked—for a while. The Pax Britannica, a long period of relative peace enforced by British naval dominance, allowed Europe to avoid major wars until World War I. However, the Congress’s conservative approach also meant that demands for democracy and national independence were ignored or violently suppressed. Revolutionary movements in Italy, Germany, and Eastern Europe were crushed by ruling powers who feared any challenge to the old order.

A Lasting Legacy

The effects of Napoleon’s reign and the Congress of Vienna shaped Europe for the rest of the 19th century. While Napoleon spread revolutionary ideals, he also showed the dangers of unchecked power. The Congress restored monarchies and created peace, but at the cost of limiting political freedom. Together, these events marked the end of one era—and the beginning of modern European politics.