One of the ways the United States justified Indian removal was by relying on older European ideas about land ownership. The most influential of these was the Doctrine of Discovery. It started in the fifteenth century when Popes issued decrees (official rulings) that allowed Christian monarchs to claim any non-Christian lands they "discovered". In 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued Inter Caetera. This decree gave Spain control over much of the Americas. It declared that Indigenous peoples did not have the same rights to their land as Christians. European nations used the Doctrine of Discovery to justify conquest, colonization, and the taking of Indigenous lands over time.

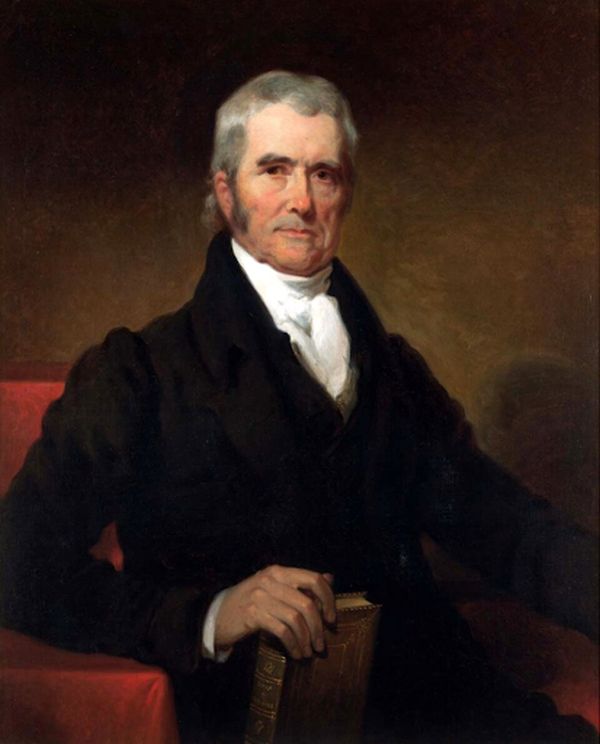

The Doctrine of Discovery eventually influenced parts of American law. In 1823, the Supreme Court decided Johnson v. M’Intosh, a case about who had the right to sell and own land in the Illinois region. The Court ruled that Native nations did not hold full title to their land. Instead, they had only a “right of occupancy.” According to the Court, only the U.S. government could buy land from tribes. Any private purchases were invalid. Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion relied on the Doctrine of Discovery. This doctrine said that the nation that "discovered" the land had the final right to it. The Court said Indigenous peoples could live on their land, but they didn't truly own it.