Indentured servants were people who agreed to work for a set number of years in exchange for passage to the American colonies. They came from Europe—mostly England, Ireland, and Germany—and made up a large part of the labor force during the early colonial period.

Daily Life and Responsibilities

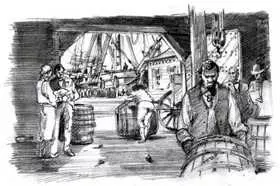

Most indentured servants worked on farms or plantations, especially in the Southern Colonies, where labor was in high demand. Others worked in towns or in their master’s home, cooking, cleaning, or doing trades.

A servant’s daily life was hard. They woke early, worked long hours, and had few breaks. Servants had to obey their masters and could be punished for disobedience. The length of service usually ranged from four to seven years, depending on the contract.

Limitations and Challenges

Indentured servants had very few rights. While they weren’t considered property like enslaved people, they were not free during the terms of their service. They could not marry or travel without permission. Punishments for running away or breaking rules were harsh—time could even be added to their contract.

Some servants died before completing their time due to harsh working conditions, disease, or mistreatment. Women servants, in particular, faced high risks of abuse and often received harsher consequences if they became pregnant during their service.

Contributions to Colonial Society

Indentured servants helped build the colonies. Their labor made it possible to grow tobacco, rice, and other cash crops. In towns, they supported businesses by working in trades and services.

After completing their contracts, some servants received “freedom dues”—tools, clothing, or land. A few were able to start their own farms or businesses, especially in earlier years of the colonies. However, over time, opportunities for former servants declined as wealthy landowners gained more power and enslaved labor became more common.

Even though they had limited status, indentured servants helped expand colonial populations, economies, and communities.