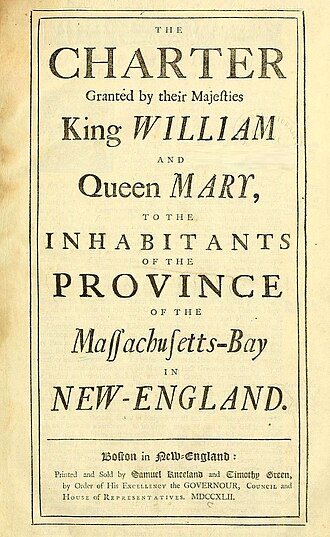

In the 1600s, the British king gave formal documents called charters to people or groups who wanted to start colonies in North America. These charters explained who was in charge and how each colony would be run. There were three main types. Royal colonies were directly controlled by the king and led by a royal governor. Proprietary colonies were granted to individuals who had close ties to the king. These proprietors were given large amounts of land and the power to appoint leaders and set up their own governments. Charter colonies, also called joint-stock colonies, were funded by investors who hoped to earn profits. These colonies were usually more self-governed and had greater independence.

Each type of colony had its own structure for leadership. In royal colonies, the king appointed a governor and a council. These officials made laws, enforced royal policy, and reported back to England. Colonists might vote for members of a local assembly, but real power stayed with the crown. In proprietary colonies, the proprietors acted like landlords or governors. They chose officials and could create laws, as long as those laws did not go against English rule. Charter colonies were the most democratic. Settlers often elected their own governors and legislatures, which gave them more say in how their communities were run.

These government differences shaped public life. In charter colonies, like Massachusetts and Connecticut, town meetings were common, and citizens had a stronger voice. In royal colonies, decisions came from the top, and governors had the final say. Proprietary colonies had a mix, depending on how involved the proprietor was. While all colonies followed English law, how much freedom they had to make their own decisions depended on the type of charter they received.

People within each colony built a shared way of life. They farmed, traded, and supported one another in towns, villages, or on scattered farms. Over time, these communities developed their own customs and identities.