The American Revolution was fought for liberty, but liberty had different meanings for different people. For white Patriots, it meant breaking away from Britain. For enslaved African Americans, it meant freedom from slavery and control over their own lives. Free African Americans saw the war as a chance to gain more rights and respect. These hopes and fears shaped their choices during the war.

In the years before the Revolution, most African Americans lived in slavery, and their daily lives were shaped by where they lived. In the South, enslaved people made up as much as forty percent of the population in some colonies, such as Virginia and South Carolina. In the North, fewer than one in twenty people were enslaved, although slavery still existed in every colony. Whether in the North or the South, laws at the time allowed enslavers to control nearly every part of life. Even free African Americans faced harsh restrictions on where they could live, the jobs they could hold, and the rights they could claim.

The ideals of liberty and equality became powerful tools for African Americans to challenge their situation. Enslaved people and freedmen petitioned colonial governments, pointing out the unfairness of colonists demanding freedom from Britain while denying it to others. Some white Americans, such as Abigail Adams, acknowledged the unfair situation, although it rarely led to policy changes. The debate over freedom and rights was no longer just about politics. It was about the lives of thousands of people.

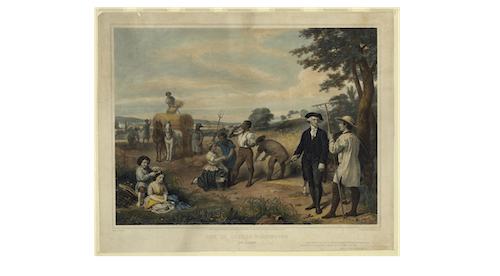

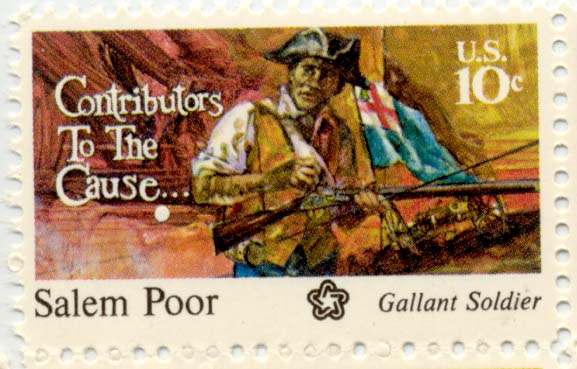

When war began in 1775, African Americans were already part of the fight. At battles such as Lexington and Bunker Hill, men such as Salem Poor and Peter Salem earned praise for their bravery. At first, the Continental Congress banned African Americans from enlisting. Shortages of soldiers and the proven skill of black troops led to a change in that decision. By the late 1770s, many northern states actively recruited African Americans, sometimes offering freedom in return for service. The First Rhode Island Regiment became famous for the large number of formerly enslaved men in its ranks. Black soldiers served in integrated units and worked as infantrymen, wagon drivers, cooks, and in other jobs.

African American women also contributed to the Patriot cause. They worked as laundresses, nurses, and cooks in army camps, often earning small wages or better rations. For some, the disruption of war brought an opportunity to escape slavery. Some women made dangerous journeys to British-held territory or to communities where they could live as free people. Many risked everything to protect their children from a lifetime in bondage.

Not all African Americans chose the Patriot side. The British promised freedom to those who escaped rebel enslavers and joined their forces. Thousands of African Americans traveled to British camps, where some served as soldiers, laborers, guides, and spies. Others worked building fortifications, carrying supplies, and tending to the sick and wounded.

By the end of the Revolution, thousands of African Americans had fought, labored, spied, or escaped in pursuit of liberty. Their actions were guided by the same revolutionary ideals that inspired the new nation, even though those ideals were not yet extended equally to all.